What stuck in my mind after reading The Black Swan (a book)13 min read

Recently I’ve felt pretty bored and want to find something interesting to read. My initial plan was not about reading a whole book but rather just some Wikipedia article. But somehow along the way, I stumbled upon a biography of a person whose work is really relevant to my interests lately, then I kept digging and finding out he is the author of several books including ‘Black Swans: The Impact of the Highly Improbable‘, with the metaphor and abstraction in the title, it captured my attention to read the first few pages and then eventually it took me almost one month (with some interruptions) to engross in this over 300 pages book. This blog post is not exactly a review, because this book is popular enough that there are dozens of reviews you can easily find on the internet. Rather, the main purpose of this post is to document my learning and what truly stuck in my mind that I want to share. If you’re still interested, then please give me your attention for a few more minutes.

After reading the first chapter, I couldn’t put the book down and kept reading because I felt some sort of novelty. However, the more I read, the more I felt I was in cognitive dissonance, the big picture seemed clear, but his stories and the way he tried to convey the message were engaging but equally dismissive. It raised so many questions in my head since he challenged the conventional thinking of the whole social science discipline and attacked them relentlessly. He thought people working in the domains (economics, politics, laws, etc…) were too theoretical with their phony mathematics and pseudoscience. He said that ‘intellectually sophisticated characters were exactly what I looked for in life‘, that’s why he mentioned around 100 different people including notable scientists and philosophers in his book, he’s good at keeping the impression and remembering names but also at showing a condescending tone for most of them (even Nobel laureates couldn’t get out of this endeavor). However, don’t let this alone detract from the profound lessons you can derive from the book.

Giving some context, the main idea in this book is about uncertainty, randomness, and the extreme impact of highly improbable events, he perceived this world is far more complicated and random than we realize, and that’s why he had fierce opposition towards planning and prediction for irregular matters (such as the economic projection, military and political events, etc…). Professionals working at predicting these irregularities are far away from so-called “experts”, and he illustrated that economists and people with PhD didn’t perform any better than undergraduates in making accurate predictions. It also suggested that the world would even a better place if you don’t know what the bell curve or normal distribution is. According to his logic and observation, the Gaussian distribution (bell curve) ignores large deviations, meaning that most of the occurrences are close to the average, and extreme values that are far away from the mean are never likely to happen, which gives us a false sense of security and underestimation of risks. This limitation in conventional predicting models is evident in many astonishing events such as the Sinking of the Titanic, World War I, the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the 9/11 terrorist attack on the US, and the rise of the Google and internet. All of them were highly impact events, some transformed people’s lives, and some were disastrous. Taleb’s skepticism against large-scale prediction (not all kinds of prediction) stems from the nature of his work, he has been working as a quantitative trader for more than two decades and researching philosophical and practical probability problems. He knows that this kind of prediction is mostly useless and nonsensical in practice. For him, probability is not just about mathematics but also has implications in philosophy and real life, which can be a valid motivation for why he wrote this book.

I think it’s enough to give you some introduction, now let’s take a deeper step into the details, in which Nassim Nicholas Taleb brought us to some different interesting concepts and how he could use insightful sentences to justify his ideas.

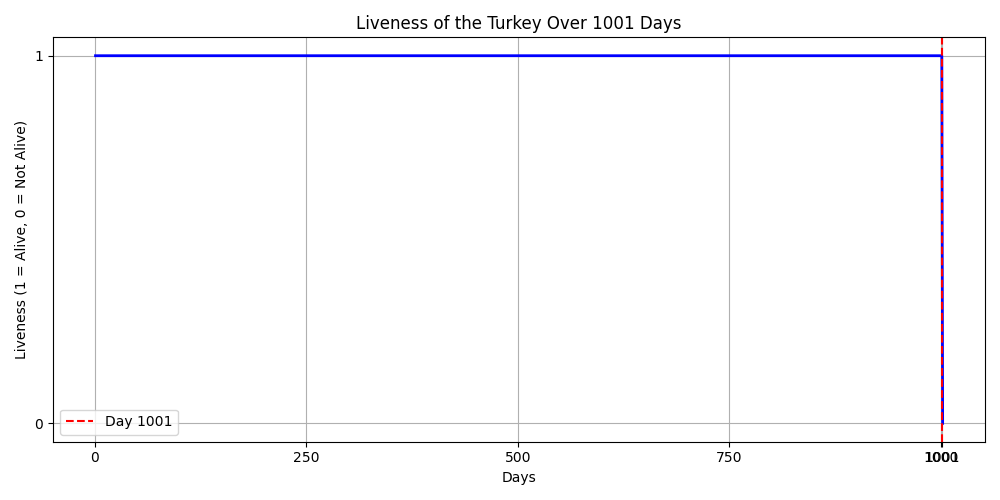

He started his book with a classical example of a black swan. For a thousand years from empirical evidence white swans were the only kind of swans that were ingrained in people’s perception, if it was a swan, then it must be white and it couldn’t be something that looked different. But then it came to the discovery of Australia, where the first instance of a black swan was sighted. Even with just a single black swan seen, it was sufficient to refute the statement that all swans were white, even though that belief was held for centuries and there are millions of white swan individuals. From this very first example, he wanted to point out that it just needs a single evidence to prove a statement is wrong, but even though there are millions of examples verifying the statement doesn’t necessarily make it correct. He provided more examples to reinforce this idea, he described the fate of a turkey as in 1000 consecutive days it was fed well and lively, the more days it had lived, the more confident that it thought it would continue living the next day since the past evidence was so assertive. Surprisingly, on the 1001st day, it was Thanksgiving day the turkey was slaughtered and eaten at dinner, so it lost its life! Once again he reaffirmed his belief on the problem of induction, where people often confuse the absence of evidence with evidence of absence.

To further develop his ideas, he then classified two types of randomness, which are non-scalable and scalable corresponding to two groups Mediocristan and Extremistan. In the Mediocristan world, when the sample is large enough, no particular events can significantly change the aggregate, meaning that if there is an exception in the sample, it doesn’t matter that much when considering the big picture. However, it’s a completely different story in the Extremistan world, where a single outlier can disproportionately impact the whole sample. An event is a black swan event if it has 3 following attributes: unexpected (rarity), extreme impact, and only explainable after it has happened. In the former type of randomness, there is no possibility for a black swan, but for the latter, it is.

How do we know which situation is considered non-scalable and which one is scalable? The author has given us some examples of both of these groups. Let’s say we have a group of people and we want to find out the total weight of all examined individuals, you can try to bring people from different races like Asian, Hispanic, Black, White, etc…to the party, or you can also invite the heaviest biological human to your experiment. When the sample is large enough, the weight of the heaviest person is inconsequential to the weight of the whole sample even though it’s quite daunting to look at this person individually. When the sample has 10000 individuals or more, the impact of exceptions would be vanishingly small, so we can conclude this measurement indeed comes from the Mediocristan world.

On the other hand, if we gather a group of people and compare their net worth with the whole sample then does this belong to Mediocristan? Of course not, if there were 1000 people in the sample and one of them was Bill Gates, we would optimistically assume that 999 other individuals each make around 1 million dollars, then we have 999 million dollars, but Bill Gates’s net worth still presents at least \(99\%\) of the whole sample since he worths around 127 billion dollars (as the time of writing this post). To make it more staggering, the richest man in the world at the time of writing this post has a net worth of 233 billion dollars, and this amount of money is equal to the whole GDP of an African country with a population of more than 200 million people!

The effect of non-scaleable and scalable randomness also applies to different professions. In some of them, you get paid because of your continuous effort rather than the quality of your decisions, if you want to get more profit, the only way to materialize that is to work more hours, but it is always subject to gravity. You can think of some of them including cab drivers, consultants, dentists, freelancers, etc…they are non-scalable occupations. On the other hand, there is no direct correlation between the time that you put in and the outcome that you have in scalable professions, the more effort you put in doesn’t necessarily mean that you gain more profit, and sometimes you don’t have to do anything extra but still live financially independent for the rest of your life because there are no real limits. You can think of these people making passive income from their accumulated work, we can easily list some of the occupations that match like Youtubers, book writers, stock owners, investors, startup owners, venture capitalists, etc…The latter kind of profession seems lucrative, but it’s only good if you’re successful since it’s definitely more competitive, and usually subject to the winner-take-all effect.

A tangle of concepts introduced, from a Black Swan, randomness, predictions, risks, bell curve, scalable and non-scalable. Let’s connect the dots to make a clearer picture of them all. A Black Swan is a result of randomness, where no discernable sequence or rules can assert with absolute certainty that some outcome must happen. And when you try to predict something that’s random, then it’s just a matter of luck because there is no certainty. With that in mind, then we can get a sense of why Taleb has an aversion against predictions in social science like economic forecasts, political predictions, or sociological trends because the models they have built for these predictions are far from complete since there are too many factors we know and might not know that can influence the outcome, and just a small change in the input can completely distort the eventuality. Why does this matter? Predictions in these topics are often related to scalable matters where there is no limit and are black-swan-prone.

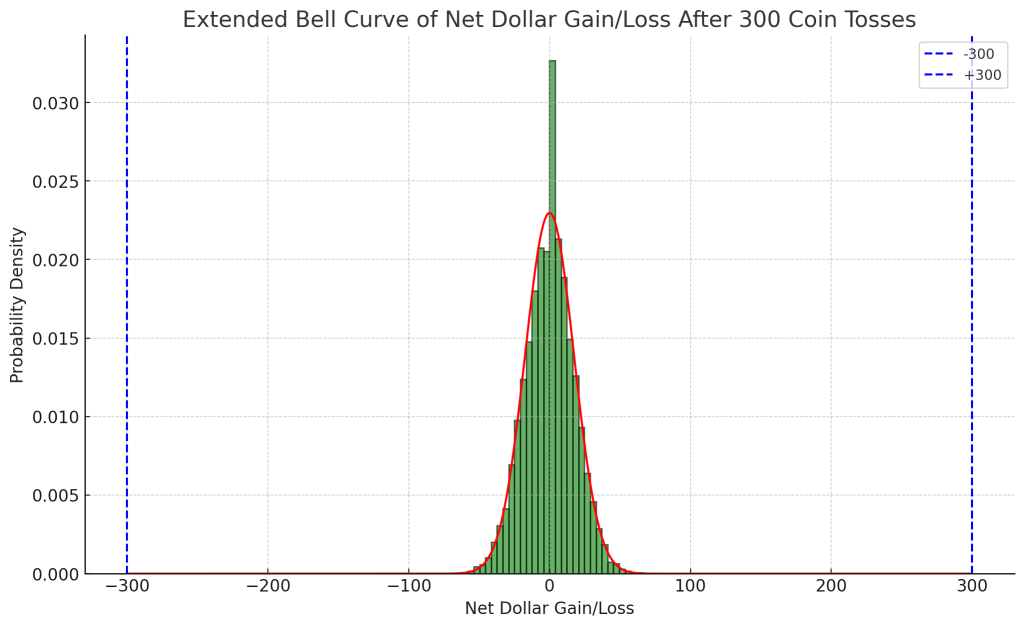

To make it more obvious why these predictions might fail, let’s play a small experiment in which you toss a coin, if it heads you get $1, and if it tails you lose $1. On the first try, you either win $1 or lose $1, so there are 2 outcomes, On the second try the number of outcomes will be doubled, and on the third try it will be eight, each time, if there are N tries, then there will be 2n outcomes. So if we have 300 tries, there will be 2300 outcomes and the odds of winning $300 will be \(\frac{1}{2037035976334486086268445688409378161051468393665936250636140449354381299763336706183397376}\), which is improbable, and if we try to draw a diagram for 300 tries and measure our gain and loss then it will look something like this:

This bell curve is symmetric, meaning the chance of winning $300 is the same as losing $300. As you can see the probability of getting $300 into your pocket is closely zero, theoretically, you could spend all the lifetime of the universe tossing the coin and then doing the same in another universe.

If you’re familiar with this kind of distribution, there is another term standard deviation (or sigma) usually comes along with it. We can understand the unit of standard deviation indicates how many percent of possible outcomes it can cover, the more unit of SD, the more unlikely the outcomes associated with this will happen. From Gaussian rule, 1 SD can cover \(68\%\) of the outcomes, 2 SD covers \(95\%\) and 3 SD covers \(99.7\%\), for 4 SD will it be \(99.994\%\) and now we have at most \( 0.006\%\) for 5 SD and above and the odd of winning $300 in the experiment above will have around 17 SD! So we can safely believe that it would never happen. However, in reality, before the existence of Google, who could ascertain that there would be a search engine that has monthly users of billions? Before J.K Rowling came up with her brainchild Harry Potter, who could imagine there would be some author whose books have 600 million copies worldwide? What was the probability of the financial crisis in 2008 to happen? If we really try to put the bell curve into these cases, since it looks at the empirical evidence and past data, the possibility of these events happening is zero if it never happened, or likely zero with too many standard deviations or something looks like the probability of winning $300 in 300 tries! But again, reality gave us a different story, it didn’t take a lifetime of the universe to make these events come into existence.

Throughout this book, Taleb mentioned quite a lot about Karl Popper, an Austrian philosopher whose idea is that a theory in empirical science (a kind of science that gathers evidence based on real-world experience and experiments) can never be proven but can be falsified. Also, there is a difference between know-how and know-what expertise, the former type refers to practical knowledge or expertise in performing some tasks, you can think of a neurosurgeon who knows how to perform a surgery. For the latter, it refers to theory or factual knowledge like an economist knows what historical financial trends and statistical models suggest.

After all, what can we get from here if we’re some regular people who do not give any predictions on social science subjects? How we can live in a world that is full of uncertainty and how it can affect our decisions? The main lesson here I think is that we make decisions and questions based on whether the subject is non-scaleable or scalable. Just think for yourself about the difference. For small things like having a picnic, hanging out with friends, starting a new hobby, or shopping, etc…you don’t have to think or question too much. But we should be wary of something that can involve a lot of uncertainty like economic forecasts, stock markets, cryptocurrency investments, etc…So favor practicality over theoretical knowledge, be a skeptic on the right matters, keep an open mind, and be a fool in the right place.

There are unknown unknowns out there that we cannot imagine, in which we don’t know what we don’t know. Then how should we prepare for unexpected and massive impact black-swan events that pop out of nowhere? The very first strategy that Talab mentioned is the Barbell strategy which involves extreme caution and extreme risk-taking, meaning that we should put most of our investment in very safe assets and small bets in highly speculative ones. Be prepared, both positive and negative black-swan events could happen in our lives, so keep learning new things broaden our perspectives, and work hard on something that we truly value to get contingency into our lives. Chasing opportunities and maximize the exposure to them and try something new when you have a chance to do so. The original idea of the butterfly effect was that when there is a small change in the initial conditions can lead to large differences in later states, but this concept also has implications in our daily life, like consistently small positive changes in our daily habits (initial conditions) can lead to different vastly different outcomes later in our life (later states). In the end, life is serendipitous! Just be curious and let luck play its role.